All teachers and leaders across Australia are looking for ways to improve their students’ learning. A common struggle is trying to ensure that all students are being reached at their point of learning. This can be difficult as students come into the classroom with different learning needs regardless of their age. A recent addition to the Teaching & Learning Toolkit is within-class achievement grouping. This approach describes how grouping students according to their current achievement in a subject can help progress their learning by an additional three months. Although this is a promising approach, further studies need to be undertaken to increase the security of the evidence.

Being in touch with the needs of teachers and principals

I attended the Mathematical Association of Victoria Conference 2018 – Teachers Creating Impact in December, presenting alongside Ollie Lovell who is the Senior Mathematics Head of Department at Sunshine College. Evidence for Learning often collaborates and presents with teachers and leaders. This is so we never lose site of two of our values of being practical and empowering to the profession. In one conference session teachers were discussing how they modify their instruction to meet the needs of their students. We know that in Australia, the variance of student achievement within one classroom can be several years and that this distance between students’ learning grows over time (Goss, Sonnemann, & Emslie, 2018). One approach that can help with meeting the needs of all students is within-class achievement grouping.

The difference between within-class grouping and setting or streaming

Within-class achievement grouping involves organising students within their usual class for specific activities or topics, such as literacy. Students with similar levels of current achievement are grouped together, for example, on specific tables, but all students are taught by their usual teacher and support staff (Teaching Assistants or Integration Aide). The aim of this type of grouping is to match tasks, activities and support to students’ current capabilities, so that all students have an appropriate level of challenge. Whereas setting or streaming, is where the students are placed within different classes dependent on their current achievement. The difference being that students stay within the same class when within-class grouping is used.

The impact of within-class achievement grouping

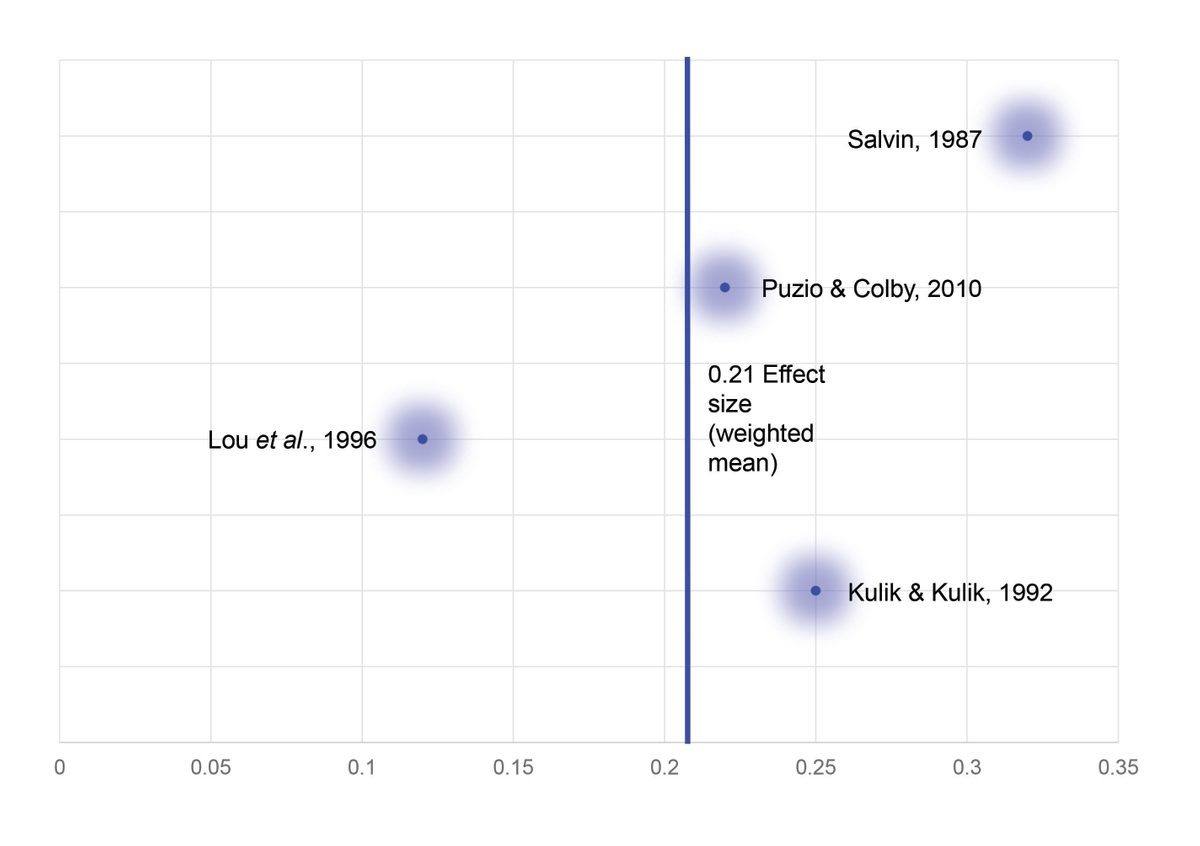

The weighted mean effect size for within class achievement grouping is 0.21 which is translated into three months of learning impact. We make this effect size translation to months’ of learning impact as we see this as being a more practical measure for educators. The weighted part is important, as this signifies that we are adjusting for the size of the population in each study to increase the accuracy of the effect size (if you want to read more about this exciting topic see our blog – The Magic of Meta-analysis).

The security of the evidence for within-class achievement grouping

The evidence security rating for within-class grouping is two padlocks, indicating that there is currently limited evidence available for this approach. Limited evidence is defined as at least one meta-analysis or systematic review with quantitative evidence of impact on achievement on cognitive or curriculum measures.

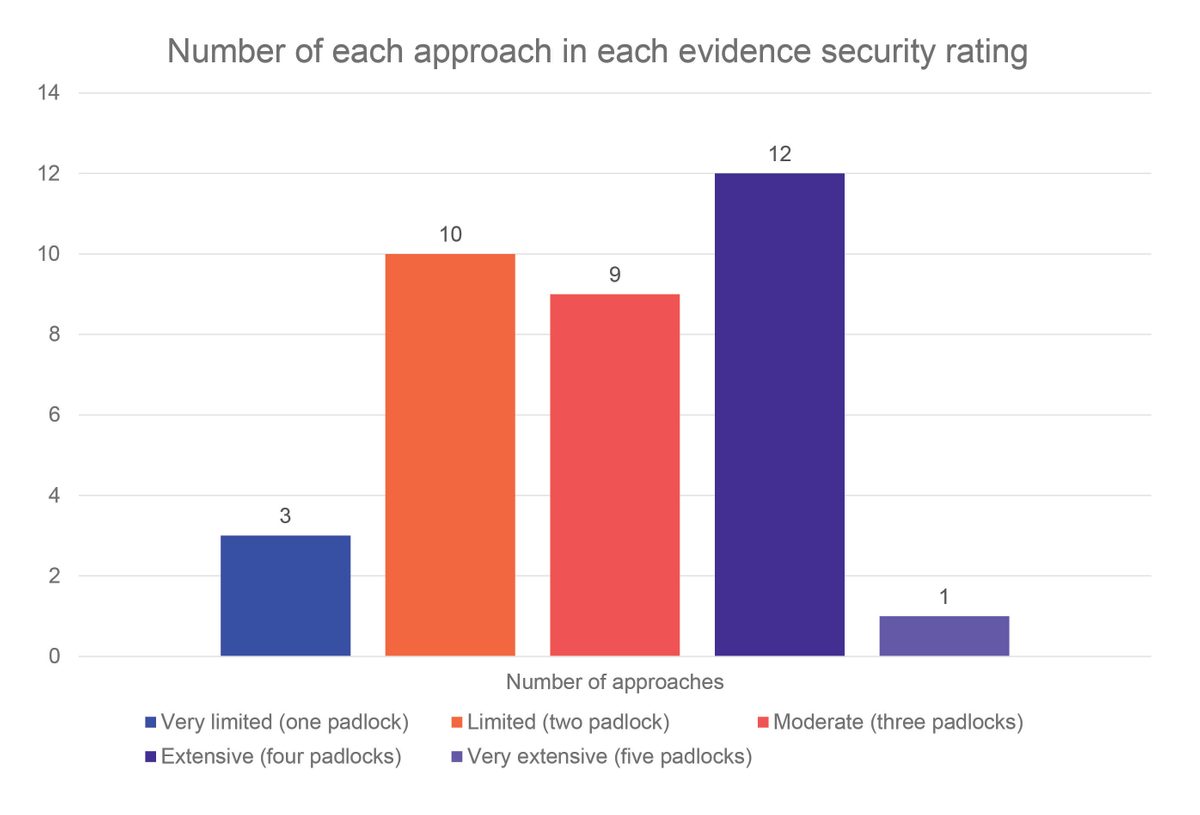

To give you an idea of spread of evidence security within the Toolkit, there are currently nine other approaches out of 35 within the Toolkit that have two padlocks and another three that are classified as one padlock. The spread of evidence security within the Toolkit can be seen in Figure 1. The other 22 approaches have a rating of three or more padlocks. The higher the evidence security the more we can trust the impact on learning outcomes.

Figure 1: Spread of evidence security for within-class achievement grouping effect size

As you can see in Figure 2 there are only four studies that meet the stringent requirements for inclusion in the Toolkit. Prior to studies being included in the Toolkit they are screened twice, first on abstract and title only and then on full text. Studies are excluded by the following criteria (Education Endowment Foundation and Durham University, 2018, p. 16):

- Topic: the study is excluded if the topic of the study is not relevant to the approach.

- Sample: the study is excluded if it does not contain data for either Early Years (2−5) or school age children (5 to 18).

- Type of outcome: the study is excluded if it does not present data on either standardised tests, cognitive tests or schools assessments including national tests or examinations, or researcher designed measures of educational achievement.

- Type of study: the study is excluded if it is not a meta-analysis or systematic review with effect sizes of the impact of the intervention either reported or calculable. (A separate search is done for single studies with quantitative data).

Figure 2 within class achievement grouping effect size

Considering the lower number of studies that are included with the within-class achievement grouping approach, “there is a need for further good-quality research on attainment grouping” (Mason, 2018). Evidence for Learning will also be publishing a summary of the Australian and New Zealand research on our site to complement the international review.

Conclusion

Within-class achievement grouping provides a way to work with students in small groups within their classroom, so that they are following the same curriculum. Setting or streaming is different from within-class grouping as it separates students into different curriculum and classes and has a negative impact on learning of minus one month of learning progress, while within-class grouping has an overall impact of an additional three months of learning progress. More evidence needs to be gathered on this practice as it currently has a relatively low evidence security in comparison to other approaches.

Dr. Tanya Vaughan is the Associate Director at Evidence for Learning. She is responsible for the product development, community leadership and strategy of the Teaching & Learning Toolkit.

References

Education Endowment Foundation and Durham University. (2018). Sutton Trust-EEF Teaching and Learning Tookit & EEF Early Years Toolkit: Technical appendix and process manual (Working document v.01). Retrieved from https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Toolkit/Toolkit_Manual_2018.pdf

Goss, P., Sonnemann, J., & Emslie, O. (2018). Measuring student progress: A state-by-state report card. Retrieved from https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Mapping_Student_Progress.pdf

Mason, D. (2018). Grouping pupils by attainment – what does the evidence say? Retrieved from https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/news/eef-blog-within-class-attainment-grouping-setting-and-streaming/